A Knightley knight in Staffordshire

A very old tomb for a very old knight, and historical locals in the churchyard.

I learnt to drive very late compared to most people. And once we got our car, I wanted to drive out into the countryside and see interesting places. And it just so happened that I could also drive to places connected with my family history which I never thought I’d be able to see.

I’ve lived just outside Birmingham for many years, in what was once the south of Staffordshire. One branch of my family, the Knightleys, can be traced back into the Middle Ages at Gnosall in Staffordshire, but it’s not really somewhere that’s easily reached by public transport. So once we had the car, Gnosall was high up on my list of places I wanted to see. Because Gnosall has the tomb of Sir John Knightley, my several-times great-grandfather… or does it?

Sir John’s tomb, complete with knightly effigy, lies towards the east end of Gnosall’s parish church, St Lawrence’s, on the south side. The church is beautiful and has some very impressive Norman arches, which were a few hundred years old when Sir John was buried here.

The effigy has been badly damaged - the Civil War saw to that. Above the tomb, there’s a plaque, which says:

This effigy is of Sir William Banestre who was knighted by King Edward III at the siege of Calais in 1347. This monument was damaged during the English Civil Wars.

But despite what the plaque says, experts in such things have looked at the tomb and its effigy and come to the conclusion that it’s too late to be Sir William’s. Sir John would’ve been born around the time Sir William was knighted, and the style of effigy and the armour our deceased knight is wearing suggest a date around 1410/1420 - which is when we know Sir John died.

As well as the details of the knight’s armour - which helped to date the effigy and give him his identity - you can see some interesting features (and I don’t just mean the pipes for the church’s heating system, which skirt the edge of the tomb). Rather than rest his head on a helmet, Sir John is lying on a pillow, and also an angel, whose head has been lobbed off (presumably by a Roundhead who thought the angel was too Catholic).

You can see his helmet lying to one side, along with centuries of graffiti carved into him, which seems rather undignified. His hands and the lower half of his arms are lost, as are his feet.

But you can still see the lion which he was resting his feet on. I don’t know about you, but I always find a miniature lion far more comfortable to rest my feet on than a cushion.

You’ll notice in the top photograph that there’s a tiny figure lying to Sir John’s side. No one’s entirely sure who it’s meant to be, and it seems that at some point, someone decided to cement it to Sir John’s tomb to stop it wandering about (I don’t mean in an E. Nesbit “Man-Size in Marble” way… hopefully…).

The Knightleys lived in Gnosall for a long, long time, and are named after the part of Gnosall where lived, called Knightley. We went to find the place, which is now nothing more than a field with some shapes under the grass to show that the moated house was there. And I managed to fall straight into a ditch full of foxgloves!

I’ll come back to the Knightleys again as members of the family moved away and their memorials appear in other churches. While Sir John looks rather battered, it’s interesting to know who numbers among his descendants: while there’s me, of course (and about half the population of my home village in Essex), there was a marriage between a Knightley and a Spencer, which means that Sir John is an ancestor of Sir Winston Churchill, and will one day be able to call himself the ancestor of a king, because he’s Prince William’s ancestor too. And yes, I expect that Jane Austen was thinking of Sir John’s descendants when she named Mr Knightley in Emma - I wouldn’t be surprised if she’d been to Fawsley (and that extraordinary place, which heraldry fans will love, is coming soon to Roads to the Past!).

Sir John’s memorial isn’t the only one of interest at St Lawrence’s. I went for a walk around the churchyard and spotted many interesting headstones, and quite a few of them are still in impressive condition. This is always a gamble, based on the quality of the local stone. If you’re looking at headstones in parts of Leicestershire, for instance, you’re in luck, because they used slate, and those look just as good as the day they were first carved. But in the Cotswolds, the soft stone wears away quickly and it’s hard to read the headstones. Gnosall’s inscriptions, however, have held up pretty well. We were lucky with the light, too, as shadows cast by even shallow inscriptions in strong sunlight make the writing easier to read.

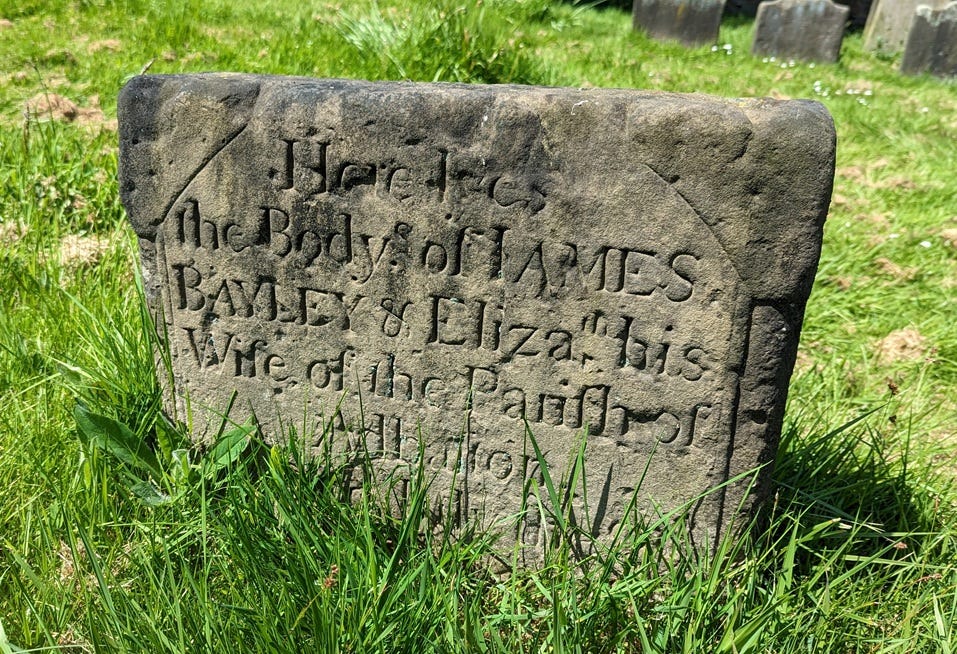

The headstone of James and Elizabeth Bayley has survived, and I think it must date from the 1700s. There’s no embellishments on it, although there may have been some on the top corners which have since worn away.

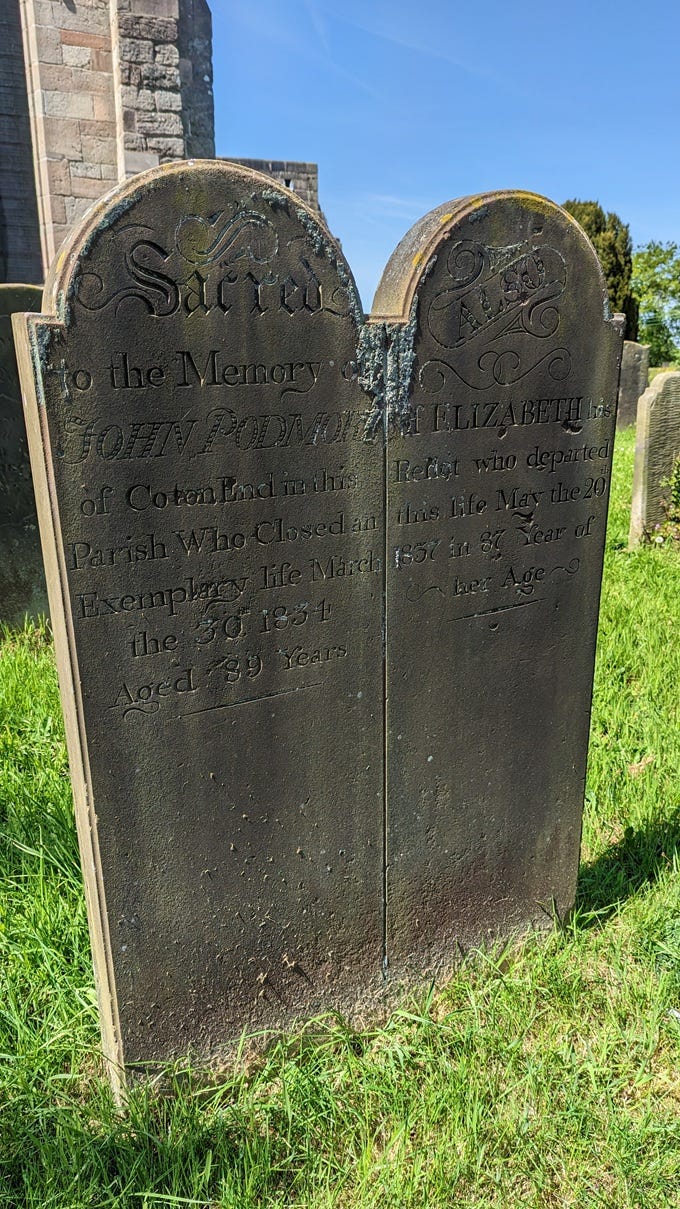

I liked this double headstone of John Podmore and his wife Elizabeth, dating from about the 1830s. You can see how well the inscriptions have survived, and the style of carving for his name is unusual. But it may be a local feature, as we can see the same here:

Samuel Wright, who died in 1832, seems to have had a headstone carved by the same stonemason!

The headstone of Jane Ashton has some interesting winged heads. She died in 1783, and the inscriptions and decoration have lasted impressively. Winged heads on memorials began life as winged skulls, descendants of Mediaeval memento mori. The skulls departed and were replaced by heads and they took on the less sinister appearance of angels. And just look at that beautiful carving - all those loops and curls.

And last but not least, I found a surprise memorial. I’m originally from Essex, and I didn’t think I’d find a connection with Gnosall beyond the tomb of Sir John Knightley. But look who I found!

In Memory of Ann Whiskin senr widow of the late William Whiskin of Maldon in the county of Essex Revenue Officer died 28th day of August 1857 aged 64 years.

It’s the grave of someone who’d lived on the Essex coast, and ended up in a corner of land-locked Staffordshire.

Ann Whiskin’s death was reported in a couple of newspapers, saying she died in Gnosall. On the 1851 census, she and her husband were living in Maldon, Essex, with four daughters. Ann was born in Somerset, while her husband was born in Theydon Bois in Essex. Their daughters had all been born in Lambeth, Surrey. It looks as though their son William moved to Gnosall, as three children of William Whiskin, a revenue officer, and his wife Jane, were baptised in Gnosall in the early 1860s. So once Ann was widowed, she moved up to Staffordshire to live with her son - and this is why she was buried there. She was certainly well-travelled.

It goes to show that you never know who you might “meet”!

I co-write WW2 saga fiction with my excellent friend Catherine Curzon under our joint pen name, Ellie Curzon.

I’ve written two books on Victorian crime and forensics, and I’ve written articles for Fortean Times and Family Tree magazine. I appeared on BBC1’s Murder, Mystery and My Family, and BBC Radio 4’s Punt PI. I live in the West Midlands with a cat who looks like a Viking.

And why not check out…?

“These violent delights have violent ends…”

Catherine Curzon is a guest on the podcast If It Ain’t Baroque…, talking about royal love amid revolution. Did love survive the turmoil? Was the throne lost forever? If they didn’t love each other, could history have been different? Tune in now and find out!

An intriguing post, from Sir John's tomb to the cemetery. I, too, enjoy reading old headstones--and imagining the stories they tell. We recently walked around a historic cemetery with several stones that simply said "MOTHER" or "FATHER," surrounded by multiple children. Possibly a family illness, but mysterious nonetheless. It's interesting that women were usually labeled as wife, mother, or widow...as your photos illustrate. Thank you for an interesting read!

Your subject-matter enthusiasm makes this an appealing read.